Pain Science Confusion

In recent years, pain science has become far more widely known, and that is leading to some interesting conversation and also confusion in the fitness, massage and manual therapy communities. Lorimer Moseley and David Butler have been charismatic and influential teachers on this issue. A good example of their work is found in the popular book Explain Pain, which uses neuromatrix theory as a theoretical background. Moseley provides a very accessible and entertaining talk about pain science in this recent DVD video.

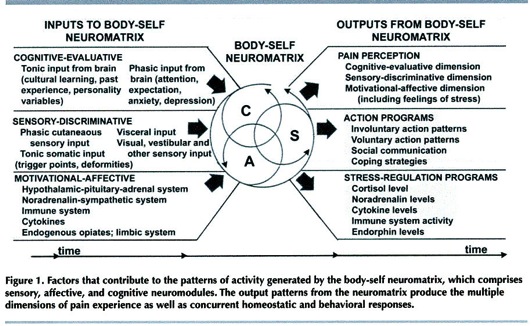

One of the primary messages is that pain is not just a “bottom up” phenomenon, where damage in the body results in “pain signals” to the brain that are reflected by the brain passively like a mirror. Instead, pain is an “output” of the brain, not an input, and it can be modulated by memories, emotions, thoughts, and other perceptions. In other words, pain is sometimes very much a “top down” phenomenon as well.

These ideas are very interesting and enlightening but also frequently cause predictable confusion and polarized debate. Here are three common misunderstandings.

Pain is in the brain?

I had an interesting Facebook conversation recently with some excellent physical therapists, including Tony Ingram, Jonathan Fass and Jason Silvernail. We were talking about the confusion that is sometimes associated with the common phrase “pain is in the brain.”

The purpose of the phrase is to communicate, in just a few words, the complex ideas described above: that pain is not a preformed sensation that arrives as input from the body, but is an output of the brain.

The problem with this phrase is that many people will read it as saying that pain is "all in your head”; or that pain is unrelated to conditions in the body; or that we should just be able to think our pain away.

Of course none of these interpretations are correct.

First, pain is very real - it is a real feeling that depends on brain activity for its existence.

Second, pain is of course related to conditions in the body. It is just not determined by them. Even though pain requires brain activity, it remains true that in many circumstances, tissue damage will almost certainly cause that brain activity. Thus, we would all prefer to have less tissue damage than more.

Third, although cognitive factors such as emotions and thoughts modulate pain, they do not determine it any more than nociception does. They can affect pain, and in at least some cases the effects can be large. But in many other cases, the effects may be insignificant, and pain may be driven primarily by nociception. Unfortunately, the processes of the brain which create pain are mostly unconscious and outside of our control. Thus, we can have a perfect understanding of the fact that pain is in an output of the brain, but be powerless to stop that output.

What is the neuromatrix?

Another semantic issue concerns use of the term neuromatrix, which sounds too fancy by half. On the one hand, it sounds like it might be referring to an earth shatteringly profound and complex concept. On the other hand, it also sounds kind of pseudosciencey, because of its similarity to the title of a certain science fiction film starring Keanu Reeves. But the “thing” to which the neuromatrix refers is really pretty simple to grasp, and no one should be arguing about whether that thing exists. The neuromatrix is simply the "combination of cortical mechanisms that when activated produce pain." Moseley (2003). No advanced degree in philosophy or science fiction required.

Does pain science imply ignoring the periphery?

No!

The “bio” in biopsychosocial refers to peripheral factors such as tissue damage. So a BPS approach does not imply forgetting the periphery.

Neither does a neuromatrix approach. The neuromatrix model specifically lists sensory input like nociception as one of the inputs that can lead to the output of pain. Because nociception is often provoked by mechanical stimuli, biomechanics matters.

Thus, these models do not neglect the role of bottoms up processes in the creation of pain. They merely add consideration of top down influences. Understanding the role of the brain does not mean neglecting the role of the body. I’ve seen a surprising amount of polarizing debates on these issues which fail to understand this crucial point.

Thus, pain science does not imply getting rid of peripheral or biomechanical treatment methods. (Provided they work!) It might, however, encourage a change in explanation as to why those treatment methods work.

Link to an a great interview

Bret Contreras recently addressed these issues and many more in an excellent interview with Jason Silvernail. If you found this blog post helpful I highly encourage you to take a look.

Bret is coming at pain science from exactly the type of background that often makes it confusing or threatening. As a personal trainer and powerlifter, he is very knowledgeable about posture, biomechanics and structure - the exact factors which pain science suggests might not be as important as we previously thought in creating pain. But Bret has clearly done his homework here and asks all the right questions, many of them concerning what degree we should worry about biomechanics. Jason's answers are very helpful to anyone looking to incorporate pain science knowledge into a biomechanical approach.

This is exactly the type of dialogue between different schools of thought that eliminates confusion and polarizing debate, while at the same time maximizing the exchange of valuable information. Thanks guys for a great job.

I hope to contribute more to this dialogue with the book I'm working on right now. I'll give a status update on that in a future post!