Better Movement in the Joint

Why does pain often occur in the joint? There's a lot that can go wrong in a joint. Here's a post on the subtle small movements in a joint that might make a big difference.

Movement at a joint requires the bones to rotate, spin, roll and slide smoothly and safely around other bones, tendons, ligaments, joint capsules, muscles, cartilage and most importantly nerves. As we age, many of these “obstacles” to safe movement become rougher and larger through injury and normal degenerative aging processes. Performing a full range of motion movement at a joint without bumping or grinding any of these obstacles might require a very subtle and precise movement. The more accurate the movement, the less bumping and grinding. The less precise the movement, the more wear and tear on the joints, causing irritation to nerves, inflammation, microtrauma, stress, loss of energy, etc.

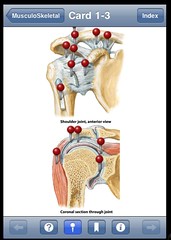

Take the example of shoulder abduction, or lifting your arm out to the side and over your head. Abduction is primarily accomplished by contraction of the deltoid muscle on the side of the shoulder. If the deltoid muscle contracts without any stabilizing help from the rotator cuff muscles, it will tend to roll the ball of the arm bone up in the shoulder socket until it bumps into the acromion process, pinching the soft tissues and nerves in between. In order to prevent this from happening, the rotator cuff muscles need to contract at the proper time, to exert a downward force on the ball of the upper arm that keeps it in the middle of the socket where it belongs. That way, the ball spins in one place in the socket instead of rolling upwards. It's a very subtle and small difference, but incredibly important because it prevents impingement, which can cause pain and injury. Of course, similar impingements or traffic jams can occur at every joint because of similarly small deviations from perfect form.

So how do we train precise joint movement? One simple way is by paying very close attention to what is happening in the joint during movement and using that feedback to improve the quality of the motion. This necessarily requires doing simple movements very slowly and mindfully, as in the Feldenkrais Method or Z-Health. For example, if you are trying to improve a dumbbell press, you can do the move without weight in slow motion while tuning into the subtleties of how the motion feels in the joint. You should be curious about the following questions Is there any pain with the movement? Is there even the slightest discomfort? Is the movement arc smooth or ratcheted? Do you need to speed up and use momentum to skip over an uncomfortable part of the movement? Is the movement smooth and easy or labored and filled with tension? Are you moving with the effortless quality of a great athlete, a dancer or a little child? What would it feel like to move perfectly? Do you feel tension in non moving parts of your body such as your face, jaw or hands? Can you do the movement incredibly slowly? As fast as possible?

If you grab a dumbbell after this exercise and press it you will probably notice that it feels easier and smoother than it normally does. This is partly because your brain has just received lots of novel, interesting information about what is going on in that shoulder joint during a press. In other words, you just improved your proprioception, and the brain therefore has a better map of the shoulder.

Of course you can do the same or similar exercises for other joints and movements. Some great movement programs that are built around slow, mindful and exploratory movements are the Feldenkrais Method, Z-Health, tai chi, and somatics. Yoga done properly counts as well, provided you are not placing excessive focus on quantity of motion instead of quality.